Comment 182 – comments and feedback

Back to all comments and feedback from the public

Marcus Powlowski

Feedback on the Proposal of the Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for the Province of Ontario

Marcus Powlowski Member of Parliament for Thunder Bay-Rainy River September 30, 2022

Introduction

I would like to begin by recognizing that the Federal Electoral Boundaries Commission for Ontario (the Commission) is faced with a difficult task. Ontario is a province with a population that is unequally distributed across a vast territory. And with Southern Ontario growing at such an incredible rate, this population inequality has reached a historic level. Adding to these challenges is the legislation that guides your work. Many of the criteria and definitions outlined in the Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act (EBRA) are poorly defined, vague, and perhaps even contradictory. Ultimately, a lot is left to your judgement. And no matter what you decide, many people will be unhappy.

That said, I must now present my feedback to your proposal to adjust the federal electoral boundaries in Ontario. First, I strongly disagree with the decision to reduce the number of seats in Northern Ontario from 10 to 9. Second, I disagree with the proposal to create the new – and incredibly large – riding of Kiiwetinoong—Mushkegowuk. And third, I disagree with many of the proposed boundary changes and additions to Thunder Bay-Rainy River- most importantly adding the Kenora region to Thunder Bay- Rainy River.

While I am sure the Commission has proposed these changes to improve effective representation in Ontario, I do not believe this has been achieved. My argument is that your proposal suffers because it places too much emphasis on population equality, and in doing so, ignores the other factors that are outlined in legislation and law, such as geography, manageable geographic size, communities of interest, communities of identity, and the historical pattern of electoral districts. I also believe you have made your job more difficult by creating population benchmarks that are stricter than what is established in EBRA. I mean here your decision to keep Northern ridings within 15% and Southern ridings within 10% of the population quota, as opposed to the 25% outlined in EBRA. Similarly, your decision to create an entirely new 520,307 km2 riding with only 36,325 has forced you to increase the population and size of the other ridings in Northern Ontario, thereby making them all more difficult to manage.

Having reviewed the relevant legislation, court rulings, and statistics for the region, I completely understand that there must be changes in Northern Ontario and Thunder Bay-Rainy River. Later in this submission I will outline some changes that I believe are reasonable and meet the legislative and legal requirements of the Commission. My hope, however, is that you will decide not to eliminate a riding in Northern Ontario, and will instead work with the existing ridings to find a reasonable and less disruptive compromise. In my view, this would involve allowing the majority of ridings to stay as close to 25% deviation as possible. I would also propose something a little more radical: to consider making Timmins-James Bay an extraordinary riding alongside Kenora. In my view this would be the optimal conclusion given the Commissions legislative and common law constraints.

The Right to Vote and Effective Representation

The issue facing the Commission is part of a classic Canadian dilemma: how does our country – a federation and a representative democracy - fairly represent the interests of citizens who are unequally distributed across vast distances and 13 different provinces and territories? Or put differently, how does Canada ensure our citizen's right to vote that is protected in section 3 of the Charter or Rights and Freedoms? In theory, there are two possible answers. The first is absolute parity, or the idea that one person's vote should be roughly equal in power to another person's. And the second option is relative parity, or the idea that some imbalances of voting power are required to ensure equity and fairness between groups or regions. From Canada's earliest days, the solution has been relative voter parity. This idea underpinned why smaller provinces like Prince Edward Island receive disproportionately more seats; and why ridings like Kenora or Thunder Bay-Rainy River have smaller populations than those in Toronto.

Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act

The principal of relative parity is at the heart of the Commission's enabling legislation, the Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act (EBRA). note 1 While section 15(1)(a) of EBRA states that the primary rule governing the establishment of electoral boundaries is population equality, section 15(1)(b) states that several other factors must also be considered, such as:

- the community of interest or community of identity in or the historical pattern of an electoral district in the province, and

- a manageable geographic size for districts in sparsely populated, rural or northern regions of the province.

Section 15(2) also states that "The commission may depart from the application of the rule set out in paragraph (1)(a) in any case where the commission considers it necessary or desirable to depart there from:

- in order to respect the community of interest or community of identity in or the historical pattern of an electoral district in the province, or

- in order to maintain a manageable geographic size for districts in sparsely populated, rural or northern regions of the province.

And finally, Section 15(2) concludes by saying:

"but, in departing from the application of the rule set out in paragraph (1)(a), the commission shall make every effort to ensure that, except in circumstances viewed by the commission as being extraordinary, the population of each electoral district in the province remains within twenty-five per cent more or twenty-five per cent less of the electoral quota for the province.

As these sections from EBRA clearly demonstrate, there is much more to redistribution process than population equality, there are also communities of interest, communities of identity, manageable geographic size, and the historical pattern of electoral districts. It also outlines that the Commission can allow ridings to deviate as much as 25% from the population quota, and even more in 'extraordinary' cases. I will return to these points later in my submission.

The Supreme Court and the Carter Decision

The Supreme Court of Canada has also supported the principal of relative parity in Canada when interpreting our right to vote. In 1991, the case Reference Re Provincial Electoral Boundaries (Sask) [1991]

2 S.C.R. 158 (hereinafter called the Carter decision) found its way to the Supreme Court to address the boundary distribution process in Saskatchewan. The Court was asked whether the proposed changes to Saskatchewan's electoral map, which would have resulted in variances as high as 50%, infringed on citizen's right to vote. A 6-3 majority ruled that the variations did not infringe the right to vote and that deviations from absolute voter parity may be justified under the charter.

Justice McLachlin, writing for the majority, held that the deviation between districts did not violate section

3 of the Charter. She stated that "the purpose of the right to vote in section 3 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms is not equality of voting power but the right to 'effective representation'?. This is worth quoting in some detail:

"Relative parity of voting power is a prime condition of effective representation. Deviations from absolute voter parity, however, may be justified on the grounds of practical impossibility or the provisions of more effective representation. Factors like geography, community history, community interests and minority representation may need to be taken into account to ensure that our legislative assemblies effectively represent the diversity of our social mosaic. The history or philosophy of Canadian democracy does not suggest that the framers of the Charter in enacting s. 3 had the attainment of voter parity as their ultimate goal. Their goal, rather, was to recognize the right long affirmed in this country to effective representation in a system which gives due weight to voter equity but admits other considerations where necessary. Effective representation and good government in this country compel that factors other than voter parity, such as geography and community interests, be taken into account in setting electoral boundaries." note 2

The Supreme Court's ruling on this matter suggests that equating the right to vote with the principle of absolute voter parity would be a radical departure from the more equitable notion of the right to vote that the Supreme Court said was captured by the Charter. In their view, the right to vote should be determined in a "broad and purposive way" to have regard for historical and social context, "social and physical geography", and the good governance of the province as a whole.

Post-Carter Ambiguity

The Carter decision introduced the idea of effective representation and stressed that, in the Canadian context, the right to vote is dependent on relative voter parity. To this end, the principle of population equality must be balanced with factors such as geography, communities of interest, communities of identity, and history. Although the Carter decision provided clarity on the practice of relative voter parity in Canada and its connection to 'effective representation' – the issue is still complex. Michael Pal (2022) sums up the issue nicely:

"The competing standards set out in the EBRA, nearly all of which are vague and abstract, provide the commissions with the freedom to act with something beyond the weak-form discretion than an initial glance at the legislation would indicate. The rules set by Parliament for the commissions to apply in many cases cannot be simultaneously maximized and are often in conflict. The EBRA provides ample space for commissions to select factors that they wish to emphasize and to diminish the importance of others. As a consequence, the decisions by the ten commissions in applying the EBRA are so disparate, and at times opposing, that it often appears they are not really working from the same set of rules." note 3

He concludes that "[t]he result is that the right to vote is stretched beyond any coherent meaning". note 4

Rachel Barnett and Dr. Karen Bird, one of the Commissioners, has also highlighted how the Carter decision appears to have established different grounds for deviating from relative voter parity. In her words:

On the one hand are the more conventional justifications regarding sparsely populated regions and urban-rural differences. These resonate with the so-called "Senatorial floor" provision of the constitution, and subsequent amendments to the federal seat allocation formula that have had the effect of over-representing less populated provinces, arguably to a point that is excessive. On the other hand are more contemporary concerns regarding identity politics and differentiated citizenship, and the tendency of electoral systems to permanently under-represent or exclude groups that are less territorially defined." note 5

And this is why the Commission is in an unenviable position. When considering fair and effective representation you are expected to work with relatively vague and poorly defined terms. This is particularly challenging in Ontario, which is not only large and unequally populated, but experiencing incredible population growth in the South. Politics is sometimes a game of winners and losers, and you are expected to make difficult decisions using your best judgement and the information available.

Raiche v Canada

Although the Commission has my sympathy, I think you have made your work even more difficult. One of my concerns is that the Commission has created its own standards and criteria that are more severe than those outlined in the legislation. I am referring to the Commission's choice to limit deviation from the population quota to "no more than plus or minus 10 per cent" in Southern Ontario and "within or close to within plus or minute 15 per cent" in Northern Ontario. But as mentioned above, EBRA clearly states in section 15(2) that: "the commission shall make every effort to ensure that, except in circumstances viewed by the commission as being extraordinary, the population of each electoral district in the province remains within twenty-five per cent more or twenty-five per cent less of the electoral quota for the province."

Again, EBRA and the Carter decision emphasize that the electoral redistribution process and effective representation consist of more than a strict adherence to population quotas. My argument is that, because of your own strict population criteria, you have limited your ability to be flexible. In Northern Ontario, where the ratio of territory to population is quite large, this decision has a radical impact; a difference of 10% is about 12,000 people, which means a lot of territory must be added to each of the Northern ridings. In my view this is completely unnecessary. The 25 ridings of the Greater Toronto Area average out to being -4.13% deviation from the quota. If that deviation averaged out to -10% you could easily create another riding and reduce the disruptions across the province.

I believe there is legal precedent to argue this point. In 2003 the Federal Court overturned the redistribution of federal seats in New Brunswick for failing to protect the francophone minority. In that case, the Commission had attempted to reduce variations from the quota to 10% instead of 25%, which necessitated moving several francophone communities from a francophone-majority constituency to one with an anglophone majority. The court found that the commission had erred by failing to allow greater deviations to protect minority representation. Or put differently, the Federal Court ruled that the Commission's insistence on population equality had diminished the effective representation in the area and province. I believe a similar case can be made in Northern Ontario. note 6

Geography and Manageable Geographic Size

One of my main arguments against this proposal is that the Commission has over-emphasized the importance of population equality, and in doing so, has under-emphasized the importance of other factors. Nowhere is this more obvious then with geography. EBRA states that that the Commission should endeavour to ensure that electoral districts are of a 'manageable geographic size' – and unfortunately, there is no official criteria for what constitutes 'manageable' or unmanageable. I will also mention that when Chief Justice McLaughlin ruled on the Carter decision, she referred to the importance of "social and physical geography". In my view, then, geography refers to both size and the nature of a place – the communities, the land, the nature of the economy, its governance, and other matters. My point is that Northern Ontario is not simply an empty expanse of space, it is a complex and dynamic place with – I would argue – far more pressing concerns to address than an urban Southern riding. So, when you propose to double the size of Thunder Bay-Rainy River and other Northern Ontario ridings, you significantly add to the workload of the MP, and thereby decrease the effective representation of its citizens.

Representation comprehends the idea of having a voice in the deliberations of government as well as the idea of the right to bring one's grievances and concerns to the attention of one's government representative. As noted in Dixon v. B.C. (A.G.), elected representatives function in two roles – the legislative and what has been termed the "ombudsman role".

I agree with this statement. One of, if not the biggest part of my job, is to listen to the grievances and concerns of my constituents. I would, however, suggest if constituents are entitled to truly effective representation, they are entitled to something more than a sympathetic ear. I would suggest that when a grievance is legitimate, and of sufficient importance, constituents are entitled to have their MP at least attempt to advocate for possible solutions to their problems and possibly even, dare I say it, instigate necessary changes.

Now of course an MP can not listen to every complaint let alone act on them. Nor are all complaints legitimate or amenable to solutions. Furthermore, it is perhaps unrealistic to think that the government should review its policies when confronted by the grievances of one of its 35 million citizens. But it does happen. Furthermore, the fact that it can, and does, happen is at the heart of the democratic process. Let me give you two examples of where this happened in my riding.

Shortly after I was elected in 2019, a constituent in my riding – a veteran named Robin Rickards - asked for my help. He had been trying for years to get two people whom he had worked with while serving in Afghanistan into Canada. I had no connection to Afghanistan, but it seemed like a just cause so I got involved. Two cases turned into 3, which turned into 4, then 10, then 50. Eventually, my office became a hub that was helping coordinate a network of volunteers, many of them veterans, to identify, screen, and evacuate Afghans who had worked with the Canadian Armed Forces from Taliban-held territory to a network of safehouses in Kabul. At some point the amount of work required was beyond what myself and my staffer Rob St. Aubin, and the others we were working with, could manage and the network had to formalize and become a legal entity in order to fundraise and increase its impact – this organization is now called Aman Lara, and they have now helped hundreds, if not thousands, of vulnerable Afghans escape Taliban territory. note 7 But even though my office pulled back from the day-to-day operations, we continued to advocate for a special immigration program to help those Afghans who have assisted the Canadian Armed Forces to come to Canada. Fortunately, in July 2021, the Canadian government officially opened the Special Immigration Measures (SIMs) Program for Afghans.

A second story. Even before I was elected, I was approached by Dominic Pasqualino the local head of UNIFOR at the local Bombardier plant. The plant was running out of work and soon there would be significant lay offs. Certainly, the best hope for on-going work in the plant, which was at the time the biggest private employer in Thunder Bay, was to secure a contract for 60 Streetcars that Toronto wanted to purchase. The purchase, however, would have never happened without federal and provincial funding. That too took time, but it eventually happened and Thunder Bay got the contract.

The Complexity of Rural and Northern Ridings

Of course, I was not the only one advocating for these two things, but I think my office played a part. Of note in both cases a constituent came to meet me, the MP, and their doing so contributed to the government recognizing their concern and eventually addressing those concerns. These are just two examples – one global and humanitarian, the other more local and economic – of the kind of work MPs find themselves doing. One thing I want to stress, however, is that these large ridings in the northern rural part of the province are not devoid of issues. To the contrary, I would argue that MPs of large ridings usually have significantly more issues to understand and advocate for than those in small, densely packed urban ridings. The issues in a northern riding like Thunder Bay-Rainy River are indeed numerous.

To begin, I am MP for over half of the US-Ontario border. This can create quite a few issues. There are matters relating to cross-border livestock transportation and illegal American fishing – an issue that involves the Boundary Water Treaty and the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA). This was in regular times. During COVID it has been much busier. For a region that is highly dependent on the border for trade, tourism, and leisure, the recent border closures had a significant impact. Likewise, the ArriveCAN app was another issue that resulted in a considerable amount of work for my office.

Then there is climate change. Thunder Bay-Rainy River is home to many lakes, rivers, streams, and other bodies of water. It is also part of the Lake Winnipeg watershed, the second largest water shed in Canada, as well as the Rainy-Lake of the Woods Watershed – both of which span multiple provinces and US states. With so much water our riding is prone to flooding, and this year was no exception – hundreds of homes and cottages were destroyed this spring in the Western part of my riding. People in my riding were understandably upset by this flooding, even more so because many of them did not qualify for provincial assistance, and federal assistance, where it does exist, flows through the provinces. I wish I could provide an easy answer for how we could better address the floods, but this is also highly complex. The different dams of the region are represented by different governing bodies that are constrained by international treaties and consist of membership from different technical experts, community groups, and political representatives from several different provinces and American states.

In Northern Ontario, like the rest of northern and rural Canada, economic issues are top of mind. Northwestern Ontario is a region that has been historically dependent on natural resources, which has created some challenges as the global economy has changed over time, and countries from time to time have implemented restrictive trade policies (e.g. softwood lumber tariffs). And because of our relatively remote nature, the cost of doing business is generally higher, which affects our competitiveness in national and global markets. According to Charles Conteh, an expert on regional development, the result for Northern Ontario is:

"…a high degree of vulnerability to resource depletion, volatile world commodity price swings, the roller-coaster boom and bust cycles of the resource industries, the whims of corporate decisions, and changes in the Canadian dollar exchange rate." note 8

This quote perfectly summarizes many of the trends that I see everyday in my work. Thunder Bay itself is traditionally the main manufacturing centre for the region, but because of changing economic realities, mechanization, and international trade rules, we have lost a lot of well-paying jobs. Earlier in this section I talked about Bombardier; once we were a major producer of railcars for the US market, but the 'Buy American Act' instituted under Donald Trump has made it difficult to sell to the American market. This has resulted in significant lay offs. And indeed, the Bombardier plant in Thunder Bay was ultimately bought by Alstom, a French multi-national manufacturing company. In the other side of the city, the Port Arthur Shipyards once employed 1,200 people, but in recent years has (at least at one point) been reduced to just one full-time employee.

The western side of my riding is not immune from economic woes. It has been several years now, but the mill closure in Fort Frances and the mine closure in Atikokan are still being felt. More recently, tourism operators have really struggled because of COVID and border closures that have prevented American customers from entering the country. These are just a few examples.

There are, however, some exciting new prospects for economic growth in the region. The green revolution along with changing sociopolitical realities (i.e. a desire to be less dependent on China and Russia) have lead to a global race to establish supply chains for critical minerals in friendly countries. Thunder Bay is gateway to the critical mineral deposits in the region and further north in the Ring of Fire. Three different companies are in the process of trying to open Lithium mines in Northwestern Ontario. This may also involve doing part or all of the refining in Thunder Bay.

The federal government also plays a role in economic development. In terms of mining, government assistance in financing, infrastructure, and minimizing regulatory barriers are all part of the equation when companies look to open mines and refineries. This is why our government has recently announced a Critical Mineral Strategy. Although some of our economic issues are beyond my government's control our government is implicated, at least in some way, in many of these issues. For example, although the Buy American Act has made it difficult to sell railcars to the US there is still the Canadian market. Many cities are looking to expand their public transit programs but need federal financial assistance to do so. As a result, I have advocated for permanent federal funding for mass transit. Likewise, Heddle Marine is in the process of reopening its Thunder Bay shipyards. They too have a federal government connection as federal funding for the building and repair of coast guard vehicles, ice breakers and naval defence are an important part of their business plans.

I would also argue that the federal government has an even larger role in the economic development of rural and northern Ontario. This is partly because of the governance of the region. Unlike southern Ontario, which is made up of regions and countries, Northern Ontario is divided into districts. Regions can offer a forum for planning, advocacy, and resource sharing that can assist municipalities with their economic development plans. But districts do not have the administrative authority or capacity of regions or countries – so for the many towns, townships, and unorganized areas of my riding, there is nowhere to turn except the provincial and federal governments. As a result, there is a lot of contact between MPs and local government in a riding like Thunder Bay-Rainy River. This is magnified because I have nearly two dozen towns, townships, and First Nation communities in my riding. My contact list of mayors, Chiefs, councillors, and other officials contains over 200 names. This is almost certainly more than the average urban MP in Ontario or anywhere else.

And as one of two MPs for Thunder Bay, I am also an urban MP. Thunder Bay is typical of many large cities; we have problems with crime, especially gangs. In fact, we are almost always the murder capital of Canada – a moniker I hope we can one day put behind us. Thunder Bay also has a lot more problems with drug and alcohol addictions than Southern Ontario communities. Although we certainly need more substance abuse programs, I would suggest to some extent addictions are a symptom of other underlying issues, like many of the economic ones I have previously mentioned.

In enumerating the many issues that the Thunder Bay-Rainy River MP needs to be involved in I hope I can impress upon the Committee that, given I am the only MP for a large riding, I have a lot of things to do. I appreciate that an MP in a riding like Brampton or Barrie might have more constituents, but can the Commission honestly say that they have anything close to the same number of issues to deal with? Even if they do, they typically have several other MPs to turn to for support.

Now the Commission might argue that whereas my office might have more local issues to deal with, we have fewer constituency issues like Employment Insurance, immigration, and Old Age Security. This might be true, but we must still provide the same services in multiple locations, which presents a challenge in a large riding. Currently, I have one office in Thunder Bay and one in Fort Frances. If the Commission's boundary suggestions are accepted, an office would need to be opened in Kenora as there are 25,000 people living in the area and they are 500 km from Thunder Bay. Fort Frances should also have an office as there are about 10,000 people living there, and Fort Frances is 2-3 hours from both Kenora and Thunder Bay. The same is basically true for Dryden.

The Board of Internal Economy sets the Member's Office Budget (MOB), which is the budget I use to manage my office, salaries, and other professional expenses. The basic budget for the 2022-2023 fiscal year is set at $388,000 for all constituencies. There is, however, a geographic supplement for large ridings. In my case, for a riding between 20,001 and 75,000 km2, I receive an extra $28,350. note 9 As I mentioned earlier, Thunder Bay-Rainy River is currently 39,545 km2; the proposal does not provide the exact size of the proposed Kenora-Thunder Bay-Rainy River riding, but I believe it would almost double. Depending on the exact size, however, there is a chance our riding will radically increase in size and not receive any additional resources to service the added areas.

Geographic Size

In listing the issues my office is, or has been, involved with, I would like to point out that – despite COVID and social distancing – I often have to meet people in person. Herein lies one of the biggest problems with the proposed boundary changes. Meeting constituents personally is very difficult when you have a geographically gigantic riding. The Commission proposes a 6th riding for Brampton. On a good day when the traffic is light, I am pretty sure I could drive from any point in Brampton to at least 25 MP's office. Last week I went to Big Grassy First Nation for a school funding announcement. I left at 7 am. I stopped for coffee at Tim Hortons on the way there and the way back and I stayed at Big Grassy for an hour. I got home at 9 pm.

A constituent in your proposed riding of Kenora-Thunder Bay-Rainy River would have to travel 500 km to get from Kenora to meet their MP in Thunder Bay or vice versa if the current MP from Kenora was elected. Furthermore, although many of your proposed ridings are also large, there are, I would propose, no other that have two different significantly populated areas in the riding; the Kenora region has about 25,000 people and Thunder Bay with something around 110,000 (about 40,000 of which are in Thunder Bay-Rainy River), and they are 500 km apart.

I am reluctant to get personal but have any members of the Commission driven from Thunder Bay to Kenora in the winter? When I first started talking about the new riding boundaries with people, they immediately responded with the suggestion that "you tell them to try driving from Thunder Bay to Kenora!" To begin with, to make that round trip in the winter would require someone get up in the dark and get home in the dark. Not only would you have to drive at night and worry about Moose our winters roads are often snow covered or icy. This is a particular concern when driving on the two-lane TransCanada Highway with every transport truck going east or west across the country is also on the road.

Driving long distances, especially in winter, is a real cause of angst for many. My mother for example, despite the fact that I am 62 and she is 86, still calls me regularly to make sure I get home safely after driving between communities. This is what distances mean to people in Northern Ontario. This is why I think most people from our part of the province would be genuinely angry to hear three people from Southern Ontario conclude that the geographic size of 8 of the 9 proposed ridings are "reasonable", while at the same time characterizing the inequalities in riding population size, which adversely affects the Commissioner's part of the province, as "grave".

I know that Northern Ontario is not the only part of the country where ridings are large. I am also aware that other parts of the country also experience winter. I would suggest, however, that such concerns are at least part of what lead to the requirement outlined in EBRA that ridings be of a "manageable geographic size". Again, I submit your Commission paid scant, if indeed any, attention to riding size in drawing boundaries. While the term "manageable geographic size" is mentioned only five times in the report, it is never defined; nor does the Commission explain why they find the size of their proposed ridings as "reasonable". Additionally, except for Kiiwetinoong—Mushkegowuk, you do not provide size estimates for any of the proposed ridings anywhere in the report or supplementary maps. Again, I am not exactly sure how big the new riding of Thunder Bay-Rainy River would be. What is the old saying? "If it isn't measured, it isn't managed!"

I would submit the size of the proposed Kenora-Thunder Bay-Rainy River riding is not of a manageable geographic size. If an election were held today, the chances are that it would be won by either Eric Melillo, the incumbent in Kenora, or myself, the incumbent for Thunder Bay-Rainy River. I can guarantee the that the 25,000 people in Kenora would not be happy to have to travel 500 km to meet their MP, nor would the people of Thunder Bay be happy to drive to Kenora. How far do people in Brampton, or Toronto, or London or Milton have to drive to physically meet with their MPs?

In the Carter decision, Chief Justice McLauglin argued that concerns about optimizing effective representation and good government ought to be considered when drawing riding boundaries. How easy would it be for people like Robin Rickards or Dominic Pasqualino to meet with their MP if they lived in Kenora 500km away? Now perhaps the Commission would point out that we could always have virtual meetings. That too is problematic because there are large areas in my riding where there is either no, or limited internet access. And, like most of rural and northern Canada, our riding is home to many seniors who often prefer to do things in person. But perhaps more fundamentally, why should people in Northern Ontario not be entitled to, as much as is reasonably possible, the same ability to access their MP as people in Southern Ontario.

Kiiwetinoong—Mushkegowuk, Community of Identity, Community of Interest, and Historical Pattern

One the key pieces of the Commission's proposal for Northern Ontario is the creation of a new 520,307 km2 riding that would be called Kiiwetinoong—Mushkegowuk. I applaud the Commissions desire to accord better democratic representation to Indigenous and other fly-in communities in Northern Ontario. I have spent years working in other remote, poorly accessible, communities around the world – including First Nation fly-in communities here in Canada. Having been the only doctor in many such communities, I realize the unique difficulties faced as a result of being dependent on airplanes. I also recognize the remarkable history of such communities. There are very few such places left on the earth. Places where people have lived for hundreds, if not thousands of years. We in Canada truly do not appreciate, how wonderful these communities are. Both their unique circumstances, and the plethora of difficulties fly-in communities face, justify they be accorded special consideration.

I would, however, question the wisdom of drawing a line across Northern Ontario and creating such an immense, sparsely populated riding. This is for two main reasons. First, the proposed riding of Kiiwetinoong—Mushkegowuk would truly be unmanageable in size and nature. And second, because this riding would be so large and under-populated, it has forced the Commission to make dramatic changes to other Northern Ontario ridings that also affect their own size, manageability, communities of interest, communities of identity, and history. In short, while it may be the case that the First Nation communities that fall within Kiiwetinoong—Mushkegowuk would benefit from better representation, it decreases the effective representation of all Northern Ontarians including the large population of Indigenous people living in the present Thunder Bay- Rainy River riding.

Size and Manageability of Kiiwetinoong—Mushkegowuk

First, the proposed riding of Kiiwetinoong—Mushkegowuk would not be of a manageable geographic size. Since I have already discussed the issue of size and manageability in the previous section, I will keep my comments on this matter short. If managing Thunder Bay-Rainy River is difficult, managing a riding that is 520,307 km2 and that has virtually no all-season roads would be very challenging indeed.

Kiiwetinoong—Mushkegowuk would be the fourth largest riding in the country, but unlike the larger ridings of Nunavut and the Northwest Territories, it would lack the larger, urban centers that are central to the accessibility of those places. The fly-in communities of Northern Ontario cannot be accessed from one central hub. Northern Ontario is divided into the Northwest and the Northeast for a reason. All flights to the Northwest must go through Thunder Bay, and all flights to the Northeast must go through Timmins. Thunder Bay and Timmins are a day drive apart and there are no direct flights. And once you are in the Northwest or Northeast, you cannot simply fly to the other corner – you must go back to Timmins or Thunder Bay and go around. If the MP was in Pikangikum, in the west of the riding, were to visit say Moosonee on the eastern side of the riding they would have to fly first to Sioux Lookout to Thunder Bay to Toronto to Timmins to Moosonee and such a trip would take at least a full day. It is much easier and quicker to fly from Toronto to Hong Kong.

Communities of Identity, Communities of Interest, and the Historical Pattern of Electoral Districts

My main argument about Kiiwetinoong—Mushkegowuk, however, is that it's creation - along with the elimination of a riding in Northern Ontario and the attempts to keep all northern districts within 15% deviation – decreases the effective representation of all Northern Ontarians. Clearly, the Commission has sought to improve the representation of Indigenous Peoples in government and to advance the agenda of reconciliation. I also support these goals. But I do not believe your proposal is balanced. I have already outlined why I think the riding is physically unmanageable, now I will outline how its creation impacts the communities of identity, communities of interest, and the historical pattern of the electoral districts in Northwestern Ontario.

Communities of Identity

There are many communities of identity in Thunder Bay-Rainy River: religious groups, linguistic minorities, and people of various ethnic origins. My focus in this section, however, will be Indigenous Peoples. This is not only because Indigenous Peoples have distinct legal and political rights, but because they are clearly the largest community of identity in the region, and one that has been identified by the Commission as deserving a stand-alone seat in the northern-most part of the province.

I would remind the Commission that the vast majority on the provinces 406,590 Indigenous Peoples in Ontario reside in the northern part of the province. note 10 Northern Ontario is home to several Indigenous Nations, including the Anishinaabeg, Cree, Oji-Cree, Métis, and others, as well as 105 of the 127 First Nation communities in the province. note 11 Furthermore, these individual communities are generally represented by different political organizations who work to advance the interests of members in their Nation or treaty area.

My point is that there is no easy way to cut it. There are many First Nation communities and Indigenous Peoples in northern Ontario, and any line you draw will have significant Indigenous representation on either side. For this reason, I am not sure why it is necessary to radically reconfigure the electoral map of Northern Ontario to create an entirely new riding with only 35 communities and 36,325 people.

I cannot be certain, but if your proposal is approved, I believe the new Kenora-Thunder Bay-Rainy River will have as many Indigenous residents as Kiiwetinoong—Mushkegowuk. The recent 2021 census states that 14,835 Indigenous individuals live in Thunder Bay-Rainy River and 30,665 in the Kenora riding. note 12 I should mention, though, that some people, however, believe the census does not adequately capture Indigenous presence in the city and region. For example, a recent study by Well Living House suggests Thunder Bay has between 23,080 and 42,641 Indigenous residents. note 13 The existing riding of Thunder Bay-Rainy River is also home to 11 First Nation communities and the new Kenora-Thunder-Bay-Rainy River would have 21 First Nation communities and perhaps a much larger Indigenous population than Kiiwetinoong—Mushkegowuk.

I do not wish to treat Indigenous Peoples and First Nation communities like numbers or pieces on a board. The point I am trying to make is that they, too, are affected by the loss of seat in Northern Ontario and some of these proposed changes. Although I applaud the concern about improving effective representation for the Indigenous communities in the far north of the province, I am sure the Commission would agree that the other Indigenous people in Northern Ontario are just as deserving of effective representation.

Communities of Interest

Communities of interest is perhaps the most ambiguous factor outlined by EBRA. And although there may be other interpretations, I will focus on how the economic and political communities of interest in Northwestern Ontario would be affected if this proposal is approved in its current form.

My main point here is that Kenora and Thunder Bay are distinct regions with their own economic and political character. The Thunder Bay city-region consists of the City of Thunder Bay, and places like Atikokan, Neebing, Kakabeka Falls, Conmee, O'Connor, Red Rock, Shuniah, and others. With access to an international airport, the St. Lawrence Seaway, railways, and the Trans-Canada Highway, it is the principal transportation hub in Northwestern Ontario. And for this reason, it is also the region's largest economic hub. I have already mentioned that the Thunder Bay region has a long history in the forestry sector and manufacturing. I also mentioned how the city-region is getting more involved in mining and moving toward opportunities in the green economy. These are related to broader shifts, whereby the region hopes to capitalize on knowledge-based sectors. This agenda is advanced greatly by the three postsecondary institutions in Thunder Bay: Lakehead University, Confederation College, and the Northern Ontario School of Medicine. note 14

The Kenora city-region consists of the cities of Kenora and Dryden; the municipality of Red Lake; and the townships of Ear Falls, Pickle Lake, Sioux Narrows-Nestor Falls, and some might even add Sioux Lookout and Ignace. This region's economy is distinct from that of Thunder Bay. Its key economic drivers are in tourism, recreation, as well as forestry and mining. While there is clearly some economic overlap between the regions, Kenora is far more plugged into the Winnipeg/Manitoba economic hub than sit is to Thunder Bay. Charles Conteh, one of Canada's leading experts on governance and regional economic development, argues that "…although Kenora shares the above-mentioned characteristics…These combined assets make it a distinct economic region well outside the Thunder Bay economic orbit". note 15

I would also suggest, however, that Thunder Bay and Kenora do not interact very much, and people in both communities are not very familiar with each other's problems. Given the fact that the communities of Kenora and Thunder Bay are so far away from each other, don't share very much in common, and historically had their own representative in Parliament looking after their own community's interests I can say confidently that the vast majority of people in Thunder Bay south would not be happy being represented by an MP living in Kenora and vice versa. Furthermore, I would suggest if the MP were to live in Kenora the one remaining office in Thunder Bay (i.e. the Thunder Bay North MP) would end up basically representing the whole city plus a large additional area. This would be very unfair to the people of Thunder Bay, particularly given the true population of Thunder Bay and the immediate vicinity is likely close to 140,000 people.

Historical Pattern of an Electoral District

In an area the size of Northwestern Ontario there is a lot of history, but the legislation appears to only consider the historical pattern of an electoral district; there is a lot of history here as well. But for my purposes, I am interested in the division between Fort William and Port Arthur. These are two cities with their own histories and that have both been represented by separate federal districts since 1917. And although the two cities combined to create Thunder Bay in 1970, the two former cities continue to enjoy unique personality and even a friendly rivalry. Indeed, there is still somewhat of a difference between the two. Today, Fort William – the "south side" - still has greater issues in its downtown core and has not faired as well as Port Arthur's city core in the north side.

My concern with the proposal in terms of Thunder Bay proper is the encroachment of Thunder Bay-Superior North into the traditional area of Fort William. For years, the border between Fort William and Port Arthur has been the Harbour Express Way, although the more traditional border is around the Neebin-McIntyre Floodway. The provincial electoral boundaries continue to respect the Harbour Express Way as the border between the two, at least until the Thunder Bay Express Way. I will also mention that the Commission has proposed to dissect Kakabeka Falls; I would argue that this is not necessary, and the boundaries should be drawn so that it is kept intact (and ideally kept in Thunder Bay-Rainy River).

I will leave it for people in the existing riding of Kenora to advocate on their behalf, but as the above timeline shows, Kenora has been a distinct federal riding for almost 100 years. And considering the distinct economic, political, and social nature of the two regions, I do not believe they should be merged.

Improving Indigenous Representation: A Note on the Far North Electoral Commission Report

The most difficult part of this submission is the matter of Indigenous representation. To prepare, I did my best to read the relevant legislation, case law, and even academic articles on the subject, including several written by two of the Commissioners – Dr. Karen Bird and Dr. Peter John Loewen, who are clearly two of Canada's leading experts on political representation. I learned a lot reading these papers and understand the imperative to improve minority – and particularly Indigenous – representation and participation in all levels of government. Again, I am fully supportive of these goals.

Above, I outlined some shortcomings to your proposal in terms of effect, and now I would like to make some brief comments about the approach. I know you are familiar with the Far North Electoral Boundaries Commission 2017 report that, among other things, investigated the potential of a provincial Indigenous district in Northern Ontario. I think their process was interesting. First, the province set up a commission to look into this issue alone. The Commission was made up of five people; three of whom were from Northern Ontario First Nations. The Commission accepted letters and email submissions and held a total of 2O in person meetings in both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. The Commission also attended Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN) Grand Council Treaty 3 Assemblies and had a booth at the Chiefs of Ontario annual assembly. Despite this fairly extensive consultation process, the Commission stated that they wished "it could have visited even more First Nations and municipalities". note 16

The second salient point, and this goes to the heart of what I think is wrong with the Federal Commission's proposal, is that the Far North Electoral Boundaries Commission did not take away ridings or decrease the democratic representation of other Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Northern Ontario in order to create the new ridings.

I understand you are working within legislative constraints. That said, I also know you have considerably more discretion. Quebec, for example, did host some public consultations before they even drafted their proposal – and their proposal was nowhere near as dramatic as the one for Ontario. From what I can gather, few Commissions have made such drastic proposals, and I believe the people of Northern Ontario deserve more than the bare minimum of public consultation when their political rights are put at risk.

My Proposal

Before submitting my own proposal, I would like to highlight one of the key principals of the Carter decision – that the courts should conclude that there has been an infringement of the section right to vote when "reasonable persons applying the appropriate principles…could not have set the electoral boundaries as they exist". I cannot figure out the entire Rubik's Cube for you, but I would suggest that what you have proposed is not reasonable, and that you don't need to do much to the present electoral map of Northwestern Ontario. That said, I fully understand that changes will be required in most ridings, including Thunder Bay-Rainy River.

Here are the key general elements of my proposal for Northern Ontario.

- Northern Ontario does not lose a seat. I have already discussed how the effective representation of Northern Ontarians is negatively impacted by large riding sizes, which would only become more unmanageable should one seat be removed. This seat can easily be found in the 112 seats of Southern Ontario if all those ridings were adjusted 1%. This is hardly as damaging to the effective representation of Southern Ontario compared to what has been proposed to the North.

- Kiiwetinoong—Mushkegowuk is not created and Kenora and Timmins-James Bay remain as federal ridings. In my view, there is no need to rob Peter to pay Paul, particularly when the result is an even more unmanageable and under-populated riding.

- Allow Timmins-James Bay and Kenora to be extraordinary ridings. This is my boldest idea, but I believe it is a compromise that would improve representation of rural, remote, and Indigenous communities in the north while also minimizing disruption to the rest of the region. And if the Commission was prepared to allow a single riding to be -68.84% under the population quota, why not allow the Timmins-James Bay and Kenora, which together are currently -75.59% under quota, remain intact? Kenora and Timmins-James Bay would be reflections of each other. Both would have significant northern Indigenous populations as well as larger urban centers, and any Indigenous candidate would have a real advantage in both ridings.

- Allow the remaining 8 northern ridings to stay as close to -25% deviation as possible. I do not see the need to force all the northern Ontario ridings to be within -15% when you consider the substantial challenges we face and the fact that EBRA allows it.

Now I will address my proposal for the riding of Thunder Bay-Rainy River. First, that the current boundary separating Thunder Bay-Rainy River and Thunder Bay-Superior North in the city of Thunder Bay remain in place at the Harbour Expressway. Second, that the existing boundary running East-West along Highway 11/17 stay in place and the junction where the boundary shoots north be drawn in such a way as to keep Kakabeka Falls intact and, ideally, in Thunder Bay-Rainy River. Third, that Thunder Bay-Rainy River absorb the population centers around Ignace and Sioux Lookout. This may not be welcome to those residents, but I understand the riding does need to expand to get under the 25% quota. And fourth and finally, that the rest of the east-west boundary that falls north of Lake of the Woods and Rainy River be kept in its existing place. The Kenora riding boundaries, except for the above changes, would remain as is.

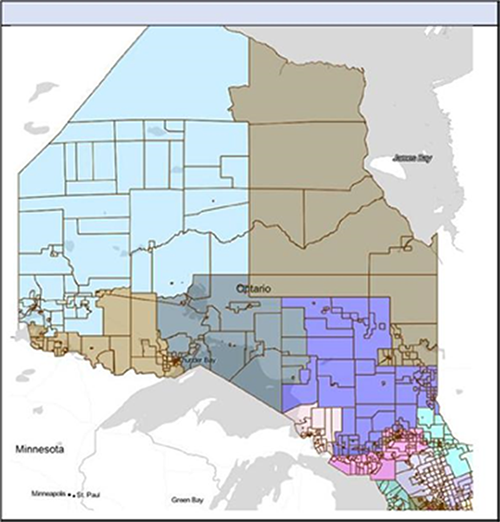

Below is a simple map I have created to give a rough approximation of my ideas. And below that is a chart showing the population estimates that correspond with the map. This map also shows how Kenora and Timmins-James Bay would look if they were made/kept extraordinary, and how the remaining ridings would look if they were allowed to fall -18-25% deviation. I must stress that this map is not sponsored by the Liberal Party of Canada, and is simply a thought experiment to show what is possible. I would note that the riding boundaries in the northeast corner of my map are somewhat arbitrary as I do not know which communities in the region have historical and cultural connections. The people of northeast Ontario, of course, are much more knowledgeable of such matters.

The Commission may well ask, if we give 1O seats to Northern Ontario where will we take a seat from? Others have already submitted, or if not will submit, suggestions as to where we could take away a riding. Is this fair to the people of Southern Ontario? Although it would be desirable to give Southern Ontario more seats, I think cutting seats in Northern Ontario in order to create ridings of slightly smaller population in Southern Ontario brings small incremental benefits, in terms of better affective representation, to the people living in large centres in Southern Ontario. It would, however, be at the expense of a considerable loss of effective representation for those living in the north. I don't think it would be that bad to accept quite a few ridings of something like 20% over the quota in the region around Toronto. I know if I had a riding where I had 125,000 constituents, but all of them in Thunder Bay, it would be far less work than providing effective representation for my present riding, never mind having to look after the Commission's proposed Kenora-Thunder Bay riding.

| 2021 Census | ||

|---|---|---|

| Riding | Population | Variance |

| Thunder Bay-Rainy River | 89,444 | -23.4% |

| Thunder Bay-Superior North | 87,943 | -24.7% |

| Kenora | 60,066 | -48.5% |

| Timmins-James Bay | 62,365 | -46.6% |

| Algoma-Manitoulin-Kapuskasing | 87,598 | -25% |

| Sault Ste. Marie | 87,908 | -24.7% |

| Nickel Belt | 92,784 | -20.5% |

| Sudbury | 94,988 | -18.6% |

| Nipissing-Timiskaming | 92,157 | -21.1% |

| Parry Sound-Muskoka | 10,4727 | -10.3% |

Footnotes

Return to note 1 Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act (R.S.C., 1985, c. E-3) https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/E-3/FullText.html

Return to note 2 Reference re Prov. Electoral Boundaries (Sask.) [1991] 2 S.C.R. 158. https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/766/index.do

Return to note 3 Michael Pal, "The Fractured Right to Vote: Democracy, Discretion, and Designing Electoral Districts," McGill Law Journal 61, no. 2 (2022): 233-274.

Return to note 4 Ibid.

Return to note 5 Rachel Barnett and Karen Bird, "Effective Representation for Whom? Visible Minorities and Ward Boundary Review in Ontario Cities," (paper presentation, Canadian Political Science Association Annual Conference, 29-May–1 June, 2017).

Return to note 6 Raîche v Canada (Attorney General) 2004 FC 679. https://www.clo-ocol.gc.ca/en/language-rights/court-decisions/raiche-v-canada-attorney-general

Return to note 7 See the Aman Lara website for more details on their work: https://amanlara.com/

Return to note 8 Charles Conteh, "Economic Zones of Northern Ontario: City-Regions and Industrial Corridors," Northern Policy Institute, Research Report no. 18 (April 2017): 1-33. https://www.northernpolicy.ca/upload/documents/publications/reports-new/conteh_economic-zones-en.pdf

Return to note 9 House of Commons, "Members Allowances and Services," https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/MAS/mas-e.pdf

Return to note 10 Statistics Canada, "Indigenous population continues to grow and is much younger than the non-Indigenous population, although the pace of growth has slowed," The Daily (21 September 2022) https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220921/dq220921a-eng.htm

Return to note 11 Federal Economic Development Agency for Northern Ontario, "Prosperity and Growth Strategy for Northern Ontario: A plan for economic development, inclusiveness and success," https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220921/dq220921a-eng.htm

Return to note 12 See Statistics Canada data table: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&SearchText=Kenora&DGUIDlist=2013A000435105,2013A000435042&GENDERli st=1,2,3&STATISTIClist=1&HEADERlist=1

Return to note 13 Jon Thompson, "Indigenous Populations in Thunder Bay and Kenora may be undercounted. Officials say that's a problem," Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (27 September 2022) https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/urban-indigenous-populations-nwo-1.6596226#:~:text=The%20same%20researchers%20analyzed%20data, time%20of%20the%202021%20census

Return to note 14 I have borrowed heavily from Charles Conteh paper on the topic of regional economic development in Northern Ontario, "Economic Zones of Northern Ontario: City-Regions and Industrial Corridors," Northern Policy Institute, Research Report no. 18 (April 2017): 1-33.

Return to note 15 Ibid.

Return to note 16 Ontario Ministry of the Attorney General, The Honourable Joyce Pelletier, "Far North Electoral Boundaries Commission," (8 August 2017) https://wayback.archive-it.org/16312/20210402050145/http://www.attorneygeneral.jus.gov.on.ca/ english/about/pubs/fnebc/